I’d like to make a slight detour and talk not about the science of exoplanets and astrobiology, but rather a particular exoplanet scientist who I’ve had the pleasure to work with.

The scientist is Natalie Batalha, who has been lead scientist for NASA’s landmark Kepler Space Telescope mission since soon after it launched in 2009, has serves on numerous top NASA panels and boards, and who is one of the scientists who guides the direction of this Many Worlds column.

Last week, Batalha was named by TIME Magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. This is a subjective (non-scientific) calculation for sure, but it nonetheless seems appropriate to me and to doubtless many others.

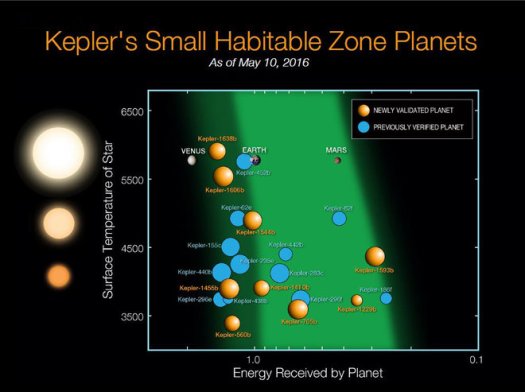

Batalha and the Kepler team have identified more than 2500 exoplanets in one small section of the distant sky, with several thousand more candidates awaiting confirmation. Their work has once and for all nailed the fact that there are billions and billions of exoplanets out there.

“NASA is incredibly proud of Natalie,” said Paul Hertz, astrophysics division director at NASA headquarters, after the Time selection was announced.

“Her leadership on the Kepler mission and the study of exoplanets is helping to shape the quest to discover habitable exoplanets and search for life beyond the solar system. It’s wonderful to see her recognized for the influence she has had on the world – and on the way we see ourselves in the universe.”

And William Borucki, who had the initial idea for the Kepler mission and worked for decades to get it approved and then to manage it, had this to say about Batalha:

“She has made major contributions to the Kepler Mission throughout its development and operation. Natalie’s collaborative leadership style, and expert knowledge of the population of exoplanets in the galaxy, will provide guidance for the development of successor missions that will tell us more about the habitability of the planets orbiting nearby stars.”

As a sign of the perceived importance of exoplanet research, two of the other TIME influential 100 are discoverers of specific new worlds. They are Guillem Anglada-Escudé (who led a team that detected a planet orbiting Proxima Centauri) and Michael Gillon (whose team identified the potentially habitable planets around the Trappist-1 system.)

But Batalha, and no doubt the other two scientists, stress that they are part of a team and that the work they do is inherently collaborative. It absolutely requires that many others also do difficult jobs well.

For Batalha, working in that kind of environment is a natural fit with her personality and skills. Having watched her at work many times, I can attest to her ability to be a strong leader with extremely high standards, while also being a kind of force for calm and inclusiveness.

We worked together quite a bit on the establishing and running of this column, which is part of the NASA Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) initiative to encourage interdisciplinary thinking and collaboration in exoplanet science.

It was NASA’s astrobiology senior scientist Mary Voytek who set up the initiative and saw fit to start this column, and it was Batalha (along with several others) who helped guide and focus it in its early days.

I think back to her patience. I was visiting her at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley and talking shop — meaning stars and planets and atmospheres and the like. While I had done a lot of science reporting by that time, astronomy was not a strong point (yet.)

So in conversation she made a reference to stars on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram and I must have had a somewhat blank look to me. She asked if I was familiar with Hertzsprung-Russell and I had to confess that I was not.

Not missing a beat, she then went into an explanation of what is a basic feature of astronomy, and did it without a hint of impatience. She just wanted me to know what the diagram was and what it meant, and pushed ahead with good cheer to bring me up to speed — as I’m sure she has done many other times with many people of different levels of exposure to the logic and complexities of her very complex work.

(Incidently, the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram plots each star on a graph measuring the star’s brightness against its temperature or color.)

I mention this because part of Batalha’s influence has to do with her ability to communicate with individuals and audiences from the lay to the most scientifically sophisticated. Not surprisingly, she is often invited to be a speaker and I recommend catching her at the podium if you can.

Batalha was born in Northern California with absolutely no intention of being a scientist. Her idea of a scientist, in fact, was a guy in a white lab coat pouring chemicals into a beaker.

As a young woman, she was an undergrad at the University of California at Berkeley and planned on going into business. But she had always been very good and advanced in math, and so she toyed with other paths. Then, one day, astronaut Rhea Setton came to her sorority. Setton had been a member of the same sorority and came to deliver a sorority pin she had taken up with during on a flight on the Space Shuttle.

“That visit changed my path,” Batalha told me. “When I had that opportunity to see a woman astronaut, to see that working for NASA was a possibility, I decided to switch my major — from business to physics.”

After getting her BA in physics from UC Berkeley, she continued in the field and earned a PhD in astrophysics from UC Santa Cruz. Batalha started her career as a stellar spectroscopist studying young, sun-like stars. Her studies took her to Brazil, Chile and, in 1995, Italy, where she was present at the scientific conference when the world learned of the first planet orbiting another star like our sun — 51 Pegasi b.

It had quite an impact. Four years later, after a discussion with Kepler principal investigator Borucki at Ames about challenges that star spots present in distinguishing signals from transiting planets, she was hired to join the Kepler team. She has been working on the Kepler mission ever since.

Asked how she would like to use her now publicly acknowledged “influence,” she returned to her work on the search for habitable planets, and potentially life, beyond earth.

“We’ve seen that there’s such a keen public interest and an enormous scientific interest in terms of habitable worlds, and we have to keep that going,” she said. “This is a very hard problem to solve, and we need all hands on deck.”

She said the effort has to be interdisciplinary and international to succeed, and she pointed to the two other time 100 exoplanet hunters selected. One is from Belgium and the other is working in the United Kingdom, but comes from Spain.

When the nominal Kepler mission formally winds down in September, she says she looks forward to more actively engaging with the exoplanet science Kepler has made possible.

Batalha’s role in the NASA NExSS initiative offers a window into what makes her a leader — she excels at making things happen.

Voytek and Shawn Domogal-Goldman of Goddard founded and oversee the group. They then chose Batalha two other leaders (Anthony Del Genio of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Dawn Gelino of NASA Exoplanet Science Institute ) to be the hands-on leaders of the 18 groups of scientists from a wide variety of American universities.

(Asked why she selected Batalha, Voytek replied, “TIME is recognizing what motivated us to select her as one of the leaders for….NExSS. Her scientific and leadership excellence.”)

This is the official NExSS task: “Teams will help classify the diversity of worlds being discovered, understand the potential habitability of these worlds, and develop tools and technologies needed in the search for life beyond Earth. Scientists are developing ways to identify habitable environments on these worlds and search for biosignatures, or signs of life. Central to the work of NExSS is understanding how biology interacts with the atmosphere, surface, oceans, and interior of a planet, and how these interactions are affected by the host star.”

She has encouraged and helped create the kinds of collaborations that these tasks have made essential, but also helped identify upcoming problems and opportunities for exoplanet research and has started working on ways to address them. For instance, it became clear within the NExSS group and larger community that many, if not most exoplanet researchers would not be able to effectively apply for time to use the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) for several years after it launched in late 2018.

To be awarded time on the telescope, researchers have to write detailed descriptions of what they plan to do and how they will do it. But how the giant telescope will operate in space is not entirely know — especially as relates to exoplanets. So it will be impossible for most researchers to make proposals and win time until JWST is already in space for at least two of its five years of operation.

Led by Batalha, exoplanet scientists are now hashing out a short list of JWST targets that the community as a whole can agree should be the top priorities scientifically and to allow researchers to learn better how JWST works. As a result, they would be able to propose their own targets for research much more quickly in those early years of JWST operations. It’s the kind of community consensus building that Batalha is known for.

She also has an important roles in the NASA Astrophysics Advisory Committee and hopes to use the skills she developed working with Kepler on the upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission.

A mother of four (including daughter Natasha, who is on her way to also becoming an accomplished astrophysicist), Batalha is active on Facebook sharing her activities, her often poetic thoughts, and her strong views about scientific and other issues of the day.

She was an active participant, for instance, in the National March for Science in San Francisco, posting photos and impressions along the way. I think it’s fair to say her presence was noticed with appreciation by others.

And that returns us to what she considers to be some of her greatest potential “influence” — being an accomplished, high ranking and high profile NASA female scientist.

“I don’t have to stand up and say to young women ‘You can do this.’ You can just exist doing your work and you become a role model. Like Rhea Setton did with me.”

And it is probably no coincidence that four other senior (and demanding) positions on the Kepler mission are filled by women — two of whom were students in classes taught some years ago by Natalie Batalha.