The triumphant Cassini mission to Saturn will be coming to an end on September 15, when the spacecraft dives into the planet. Running out of fuel, NASA chose to end the mission that way rather than run the risk of having the vehicle wander and ultimately land on Europa or Enceladus, potentially contaminating two moons very high on the list of possible habitable locales in our solar system.

Both the science and the images coming back from this descent are (and will be) pioneering, as they bring to an end one of the most successful and revelatory missions in NASA history.

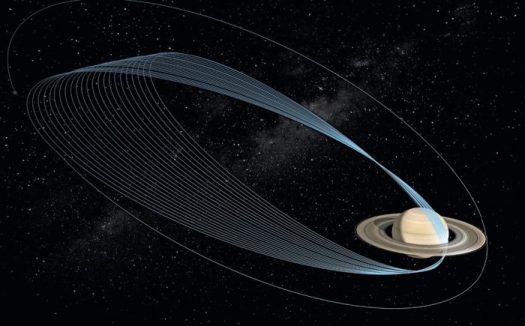

As NASA promised, the 22-dive descent has already produced some of the most compelling images of Saturn and its rings. Most especially, Cassini has delivered the remarkable 21-image video above. The images were taken over a four minutes period on August 20 using a wide-angle camera.

The spacecraft captured the images from within the gap between the planet and its rings, looking outward as the spacecraft made one of its final dives through the ring-planet gap as part of the finale.

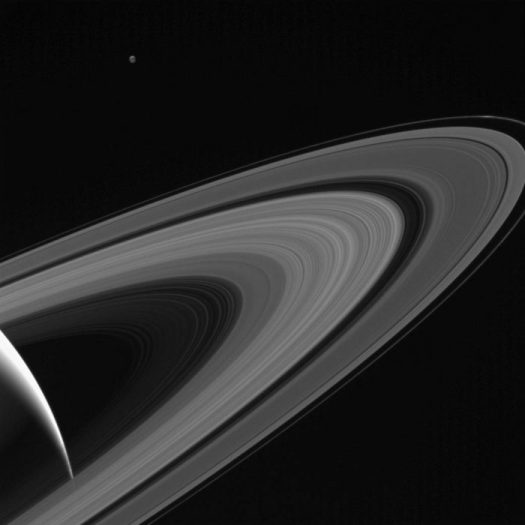

The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened. The perspective shifts from the sunlit side of the rings to the unlit side, where sunlight filters through.

On the sunlit side, the grayish C ring looks larger in the foreground because it is closer; beyond it is the bright B ring and slightly less-bright A ring, with the Cassini Division between them. The F ring is also fairly easy to make out.

While the Cassini team has to keep clear of the rings, the spacecraft is expected to get close enough to most likely answer one of the most long-debated questions about Saturn: how old are those grand features, unique in our solar system?

One school of thought says they date from the earliest formation of the planet, some 4.6 billion years ago. In other words, they’ve been there as long as the planet has been there.

But another school says they are a potentially much newer addition. They could potentially be the result of the break-up of a moon (of which Saturn has 53-plus) or a comet, or perhaps of several moons at different times. In this scenario, Saturn may have been ring-less for eons.

As Curt Niebur, lead program scientist at NASA headquarters for the Cassini mission, explained it, the key to dating the rings is a close view of, essentially, how dirty they are. Because small meteorites and dust are a ubiquitous feature of space, the rings would have significantly more mass if they have been there 4.6 billion years. But if they are determined to be relatively clean, then the age is likely younger, and perhaps much younger.

“Space is a very dirty place, with dust and micro-meteorites hitting everything. Over significant time scales this stuff coats things. So if the rings the rings are old, we should find very dirty ice. If there is little covering of the ice, then the rings must be young. We may well be coming to the end of a great debate.”

A corollary of the question of the age of Saturn’s rings is, naturally, how stable they are.

If they turn out to be as old as the planet, then they are certainly very stable. But if they are not old then it is entirely plausible that they could be a passing phenomenon and will some day disappear — to perhaps re-appear after another moon is shattered or comet arrives.

Another way of looking at the rings is that they may well have been formed at different times.

As project scientist Linda Spilker explained in an email, Cassini’s measurements of the mass of the rings will be key. “More massive rings could be as old as Saturn itself while less massive rings must be young. Perhaps a moon or comet got too close and was torn apart by Saturn’s gravity.”

The voyage between the rings will also potentially provide some new insights into the workings of the disks present at the formation of all solar systems.

“The rings can teach us about the physics of disks, which are huge rings floating majestically and with synchronicity around the new sun,” Niebur said. “That said, the rings of Saturn have a very active regime, with particles and meteorites and micrometeorites smacking into each other. It’s an amazing environment and has direct relevance to the nebular model of planetary formation.”

The view above was acquired at a distance of approximately 750,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 140 degrees. . The distance to Tethys was about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers).

The Cassini mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (the European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA and the imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

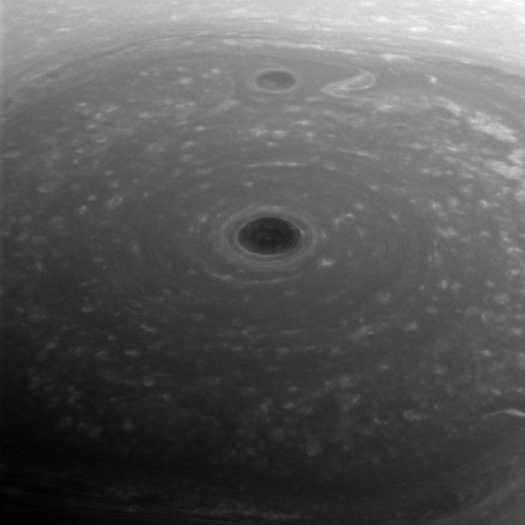

Among the areas of greatest interest during the final descent are the turbulent clouds on the North Pole of Saturn. Cassini captured this view of the pole on April 26, 2017 – the day it began its grand finale — as it approached the planet for its first dive through the gap between the planet and its rings.

Although the pole is still bathed in sunlight at present, northern summer solstice on Saturn occurred on May 24, 2017, bringing the maximum solar illumination to the north polar region. Now the Sun begins its slow descent in the northern sky, which eventually will plunge the north pole into Earth-years of darkness. Cassini’s long mission at Saturn enabled the spacecraft to see the Sun rise over the north, revealing that region in great detail for the first time.

This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 44 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers.

Saturn boasts some unique features in its atmosphere. When the Voyager missions traveled to the planet in the early 1980s, it imaged a hexagon-shaped cloud formation near the north pole.

Twenty-five years later, infrared images taken by Cassini revealed the storm was still spinning, powered by jet streams that push it to speeds of about 220 mph (100 meters per second). At 15,000 miles (25,000 km) across, the long-lasting storm could easily contain an Earth or two.

The recent view was obtained at a distance of approximately 166,000 miles (267,000 kilometers) from Saturn.

But because Saturn is a gas giant and has no defined surface per se, it’s difficult to describe exactly how far from the planet Cassini might be traveling at any given time.

On the final orbit, Cassini will plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere, sending back new and unique science to the very end. After losing contact with Earth, the spacecraft will burn up like a meteor, becoming part of the planet itself.